Two Columbia Law Students Awarded Prestigious Skadden Fellowships

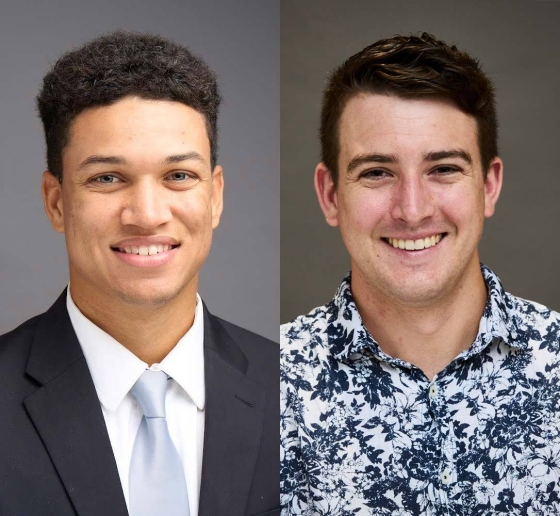

Nathan Porceng ’25 and Malik Sammons ’25 will join legal nonprofits to work on environmental and housing issues.

Two Columbia Law students have been named Skadden Fellows and will begin two-year fellowships to pursue public interest law full time this fall.

Nathan Porceng ’25 (above, right) will work on local solar energy cooperative projects for Fair Shake Environmental Legal Services in Pittsburgh. Malik Sammons ’25 (above, left) will work on litigation and public education regarding rent subsidies with the New York Civil Liberties Union. Both students are Max Berger ’71 Public Interest/Public Service Fellows at Columbia Law School.

Skadden Fellowships have been called “the public-interest version of Supreme Court clerkships.” Columbia Law is among the top 10 law schools for producing Skadden Fellows; over the past 15 years, 14 Columbia Law students have been awarded the prestigious fellowship.

“The Skadden Fellowships awarded to Nathan and Malik demonstrate that Columbia continues to be a real force for public interest and a home for students who want to use their careers to fight for justice,” says Erica Smock, dean for Public Interest/Public Service Law and Careers. “We are so proud and excited for Malik and Nathan to begin their social justice careers and are grateful for the Skadden Fellowship’s support of them.”