Franklin A. Thomas ’63: A Lifetime of Leading Change

First, Franklin A. Thomas, a 2020 Medal for Excellence honoree, worked to rebuild his old neighborhood through an innovative nonprofit agency. Then, he took on improving the world at the helm of powerful foundations.

Franklin A. Thomas CC ’56, LAW ’63, a distinguished and lifelong advocate for economic and social justice, died on December 22, 2021, in New York. In a career of “firsts,” Thomas led the philanthropic giant Ford Foundation, broke barriers on major corporation boards including Citibank, and worked to build a legal system for post-apartheid South Africa. In 2020, he sat for an interview with Columbia Law School on the occasion of his receiving the Medal for Excellence.

He calls it an “unplanned life,” but the long, eventful career of Franklin A. Thomas CC ’56, LAW ’63 has traced a line straight through some of his era’s most challenging issues.

He took on rebuilding the struggling neighborhood in New York City where he grew up when, in 1967, then-Senator Robert F. Kennedy tapped the young lawyer to head the Bedford-Stuyvesant Restoration Corporation, a pioneering community development agency. As president of the Ford Foundation from 1979 to 1996, then the nation’s richest philanthropy, Thomas focused its programs on poverty and human rights and established programs in South Africa to develop black leaders for the end of apartheid. Five years later, he answered the call to oversee the September 11th Fund, which distributed nearly $600 million in public donations to help victims of the 2001 terrorist attack.

But first, he armed himself with a degree from Columbia Law School.

For his achievements in law and his service to Columbia, the Law School will present him with the Medal for Excellence award on February 28 at Cipriani 42nd Street in New York City, along with fellow honoree Jim Millstein ’82.

Of course, his mother really wanted him to be a doctor. An immigrant from Barbados, she raised Thomas and his four older sisters in Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood and taught them to believe they could do anything: “A big project with a hefty challenge to it? That’s an opportunity, not a threat,” Thomas says.

But Thomas did not like the sight of blood. And when his mother was rooked in a real estate transaction, he realized that “to not know the law was to make you vulnerable.”

“I just felt so troubled,” he says of the experience. “You needed to know the law to be able to protect yourself and the people you care about.”

His connection to Columbia had already been formed: A high school basketball star, he passed up athletic scholarships to attend Columbia College. After fulfilling his ROTC obligation in the Air Force, he entered the Law School and took on the “demanding” curriculum. Five years later, when Columbia University began to diversify its leadership in the wake of the 1968 student demonstrations, he was named a university trustee. In 1979, the university awarded him an honorary degree.

Thomas’s legal career was brief but eventful. As a federal prosecutor under U.S. Attorney Robert Morgenthau, he prosecuted three members of the Black Liberation Front who planned to blow up the Statue of Liberty. He served as a deputy police chief under Mayor John Lindsay, then sat on the Knapp Commission investigating police corruption.

Thomas’s achievements regularly include the word “first.” He was the first African American to captain an Ivy League basketball team. (The three rebounding records he set in 1955 still stand today.) In 1969, he became the first African American to sit on the board of Citibank—a seat he kept for 40 years; and when he took over the Ford Foundation in 1979, he was the first African American to lead a major philanthropic foundation.

“Things that seem extraordinary to other people seem very ordinary to me,” he says. “That’s not self-promotion. That’s just the byproduct of some forms of experience.”

But part of his success, he says, lies in learning to spot talent. “Always get people you think are smarter than you are. First, you have to be prepared to acknowledge that there are people who know more than you do. Once you do that, [finding them] gets very easy.”

At the Ford Foundation, Thomas had the unenviable job of dramatically reducing staff and cutting programs in order to restore the foundation’s financial stability. The controversy over layoffs and killing programs was intense—some of it, he says, due to his being the first black person to lead a major foundation. But Ford needed to change to be effective, he says, and over the next 17 years, Thomas shifted Ford’s focus to human rights and urban poverty. He spun off the Local Initiatives Support Corporation (LISC) to give grants and loans to community development organizations like the Bed-Stuy group he once headed. He tripled the foundation’s endowment to $6 billion. He also expanded the foundation’s work in South Africa, where the apartheid regime had led to international boycotts. Thomas, who had led a study commission that recommended the U.S. work harder to end apartheid, says there was no risk that Ford’s involvement would prolong apartheid. The only risk would be criticism, he says. “And I thought I knew more about it than the critics."

With the blessing of Nelson Mandela’s African National Congress, the Ford Foundation funded scholarships and internships to train black professionals to work in the post-apartheid society Thomas believed would soon be achieved. Ford also funded public interest law clinics. “We were helping to reinforce black South Africans’ notion that they had rights, that they could go to court, and that they could get a favorable court ruling enforced,” Thomas said at the time. “That’s no small thing in a country that tells you you’re a non-person.”

In 1993, following Mandela’s release from prison, Thomas helped persuade Mandela and F.W. de Klerk, South Africa’s final apartheid leader, to appear together in Philadelphia to receive the Liberty Medal from President Bill Clinton—an achievement Thomas ranks among his proudest moments.

When Thomas left the Ford Foundation in 1996, he focused solely on South Africa as a consultant to the TFF Study Group, a nonprofit organization assisting development in the region. But after the terrorist attacks of September 11th, Thomas was asked to oversee the September 11th Fund, run by the United Way and the New York Community Trust. Its job was to distribute the millions in public donations that poured in to help victims of the terrorist attack. When the fund closed at the end of 2004, it had given 559 grants totaling almost $528 million.

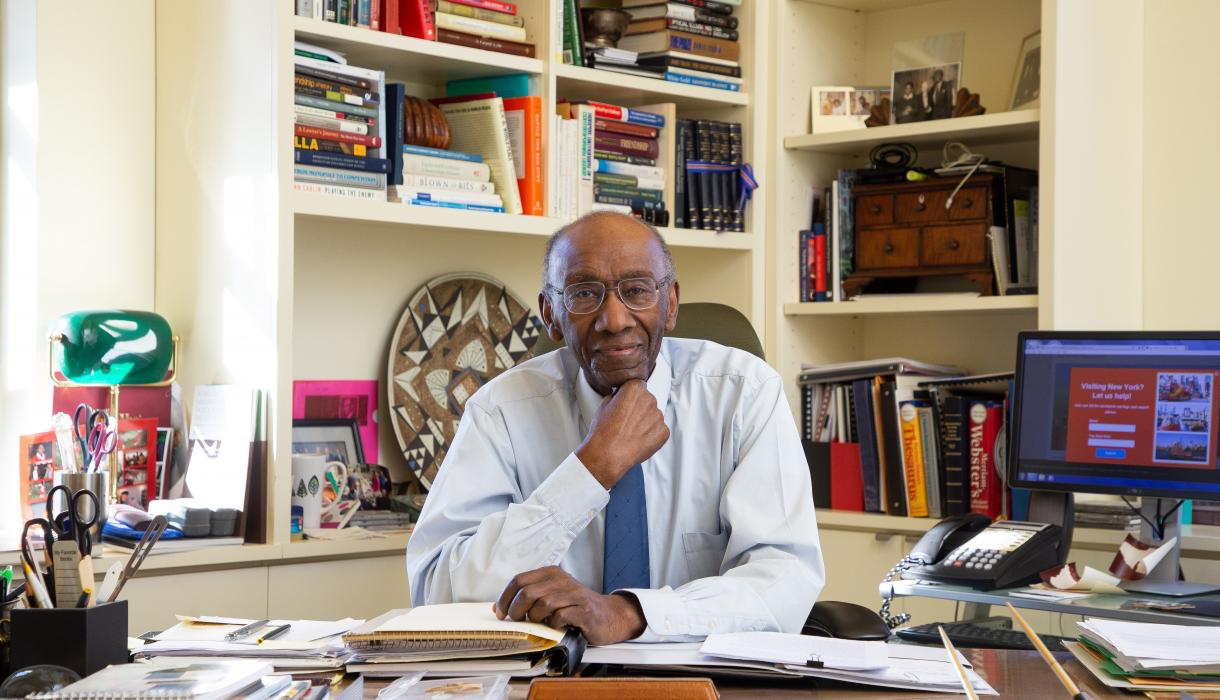

Today, Thomas’s midtown Manhattan office is filled with artwork by Mandela and photos of famous friends like Washington power broker Vernon Jordan. But despite the many awards also decorating the space, Thomas has tried to keep his own profile relatively low. “That’s exactly how I choose to be,” he says. “It’s just my style.”

As an undergraduate at Columbia, Thomas worked on an NAACP investigation of racial discrimination by landlords in Morningside Heights. He has spent his career advancing the interests of people of color, but he says his approach has differed from that of some of his contemporaries from the civil rights movement of the 1960s. Back in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Thomas’s mother taught him that when he encountered racial prejudice, he should think of it as the other person’s problem, not his.

“It doesn’t mean you don’t recognize the bad actors. It does mean that you don’t start with the assumption that everyone who looks that way is a bad actor,” he says. “That was the point that I think my mother was making to me.”

What would he tell students of color today? “Stay strong, wherever you’re going. Be clear in your own mind of the values that mean the most to you, and be unafraid to express that.” His advice for taking on challenges is equally direct: “Do what you believe is right, and do it the right way,” he says. “And take the consequences.”